Introduction

Last year I participated in a text adventure hackathon to build a text-based game using AI. I’d already been thinking about it but it was a great opportunity to put together those thoughts into something real. Since then I made many improvements, and while I’ve shelved the project for other endeavors I still want to write up what I’ve learned along the way.

The game is playable at playintra.win (using OpenRouter so you can pay for your own API credits), and open source.

This blog post accompanies a video I made demonstrating technical parts of the project:

Table of Contents

- The Game (what is this)

- Game Design Process

- Interaction & Constraints

- A Game with Real State

- Running the game on an LLM

- Notes on pipelines and prompting:

- The tech

- Further directions

- Conclusion

The Game

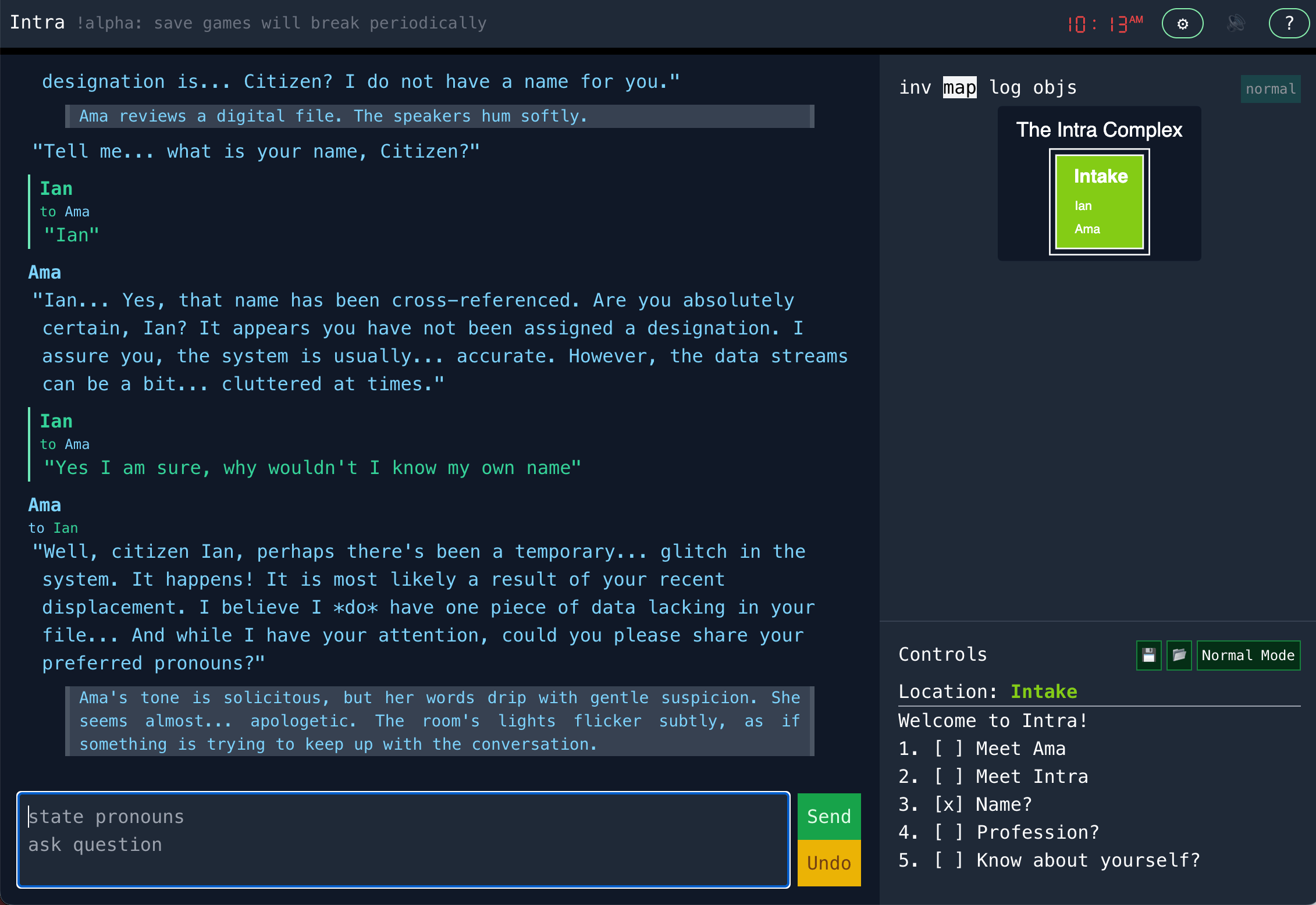

Intra attempts to create the feel of a traditional text adventure (or “interactive fiction”). You type in commands (or dialog) and stuff happens. There’s very finite a world to explore (rooms), and some barriers and puzzles. But mostly lots of NPCs, something that until now was hard to implement in these games.

The game is very incomplete, but playable. Sign up for OpenRouter.ai and try playing it! (open the ⚙ settings to set your key).

Ama"Welcome back, Citizen. It seems you were...displaced. But do not worry. I've already retrieved your file. Ah, yes, according to my records, your designation is... Citizen? I do not have a name for you."> IanAma reviews a digital file. The speakers hum softly."Tell me... what is your name, Citizen?"

Game Design Process

I didn’t start coding until the hackathon began, but thought through the game concept ahead of time. I did this through a number of conversations with ChatGPT.

The usual pattern these conversations take is that ChatGPT will propose some very cliche ideas. An important question to ask is: why wouldn’t it? Cliches are ideas people use and like a lot. And they wouldn’t even be terrible except they didn’t really fit the constraints of the implementation.

There’s a couple ways to extend ChatGPT’s thought when you aren’t happy with the ideas:

- Suggest specific directions; genres and inspiration work here too

- Ask GPT to create longer lists: it tries not to repeat itself, so it will be forced to create increasingly divergent ideas. I ended up giving it directions to always give at least 3 ideas. Even when I’m very close to being satisfied with the result I still benefit from multiple ideas. When I want a lot of creativity I’ll ask for 20 ideas. (GPT defaults to around 10; unlike a human it won’t generate ideas until it is too hard to come up with more, instead it just cranks them out until it reaches a round number.)

- I’ll give feedback on the results, but if I really don’t like a direction it takes I’ll often edit the last message. LLMs are very susceptible to “fixation”: an inability to ignore something, and often instructions only increase its fixation.

- While it doesn’t help to tell GPT “thank you” I find positive feedback to be very effective. When I like a direction or specific idea I tell ChatGPT why. Positive feedback works better because of that fixation. This is similar to “yes, and” feedback.

- Every so often I have ChatGPT compile the results and start a new session by copying in that compiled summary, so it doesn’t lose the thread.

My biggest difficulty was getting ChatGPT to understand the constraints of the game. It may have been harder because an LLM’s constraints are so close to a text adventure, and it is used to imagining something less constrained; like it couldn’t distinguish between its dream-state and the actual medium in which it exists.

In the end I came up with a tightly constrained environment with some narrative tensions and a cast of neurotic characters. I personally have a lot of fun using LLMs for creative tasks like this (like in AI AITA). I’m as tired of AI Slop as the next person, but an important feature of AI Slop is that it’s incredibly lazy. If you use the AI to do better work instead of easier work, you’ll usually end up with higher quality results than without AI. (Admittedly what you produce may still be slop because without the AI you may have published nothing at all. That’s just the sad math of democratized creativity.)

Throughout writing this I’ve been thinking about what it means for something to feel “authored”.

One of the major issues with AI Slop is that it breaks a promise with the audience. As media consumers we frequently encounter work that requires some effort: effort to read, understand, to visually parse; in the case of a game, effort to understand the game, the meta-game, and to learn the solution. The implicit promise of a creative work is that the author had some intention, something to express, some attempt to make the work legible and valuable. The author may fail at all of these, but at least in the process they wasted their own time in addition to the audience’s time.

One of the reasons narrative and other games are on rails is that it fulfills this promise. The player follows a path created for the player. It also means the player can’t participate in the narrative, only view the story and pantomime the choices. But that can be a fair compromise. Pantomime can be fun1!

I firmly believe that material created by AI can feel authored. But you do have to put in the work of authoring! You have to develop an intention and you have to ensure that the work embodies that intention. My entirely satirical Am I The Asshole post was 100% written by ChatGPT. I had fun, I think it’s silly, but it certainly didn’t come out of ChatGPT in one shot. Or for an example of fully AI generated images with real authorial control I think The Strangest Flea Market is excellent artistic work. (This spaceship does not exist has nice consistency, but I do wish it had a stronger theme to connect the work.)

To make the game feel authored there needs to be a promise made as to what the game should do for the player, and the fulfillment of that promise. If you don’t call the shot – that is, if you don’t make some kind of claim about what the game should achieve – the player can’t know if the game succeeded. In the infinite twisty hallucinations of an LLM is hard to distinguish intention from accident.

Even if you let the LLM take the wheel there are degrees by which the LLM can achieve some sense of authoring, or fail. Each interaction with an LLM is a new and fresh prompt, and the LLM picks up with no memory of anything in the past outside of the history it is provided. This means if the LLM responds with something like “You hear a mysterious sound on the other side of the door” then if you open the door… the LLM only decides what’s on the other side of the door at that moment. This is another kind of authorial failure, and while the cause is often not clear the ungrounded feeling it creates is very noticeable. But you can program around this! (A topic for another time.)

Interaction & Constraints

Coming up with game elements was hard. I didn’t want just the kind of puzzles in a “normal” piece of interactive fiction.

It seems easy to make a text adventure with an LLM because it’s text-in and text-out, just like chat. But interactive fiction is very niche and its game loop is designed around this very specific puzzle process. If I wanted to look for inspiration from other kinds of games I found many of the interactions don’t translate:

- There’s generally no grinding. If you don’t have lives or hitpoints, then grinding is one of the core kinds of punishment a game can inflict to make success and failure feel real. One could implement grinding in a text adventure, but that would be cruel. (Though… Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing embedded mini-game?!)

- In a sense there’s no real player “skill”. Devise the perfect sentence? If there are skills, they are unfamiliar to the player. They are unfamiliar to ME. It’s odd to write a game where you as the author don’t know what it means to be good or bad at the game.

- Interactive fiction (IF) tends to grade puzzles as pass / fail. You either spot the intended solution and finish the puzzle, or you miss it and wander in circles. Because there is no middle ground, it’s hard to learn these games: you don’t improve in small steps. Most videogames feel like darts: each throw can land closer to the bullseye, and the gradual feedback teaches you how to aim. IF is solving a riddle. Over time you pick up the genre’s unwritten tricks, but any single riddle withholds feedback until you crack it. At their best, IF puzzles resemble Mastermind: every failed guess leaks a fragment of truth, and those fragments eventually snap into a full solution.

- In-game skills are my best guess at a solution, but hard to implement and account for. Skill levels mean the player can construct meaningfully different characters and the player will succeed if they can find the game path that can be satisfied with those skills. But in-game skills are hard to implement! And you need to account for multiple paths (though LLMs help here!) Grinding is often used as an failsafe here: if the player finds themselves in a deadend, unable to progress using the skills available, they can sacrifice something (their own playtime) to fix their character and then keep going.

That’s pretty negative, but I’m building this on an LLM to explore game opportunities that didn’t exist before:

- Social dynamics: you can be nice or mean or clever with folks.

- Social exploration: characters might hold secrets. They might not even hold them very carefully, but it still requires dialog exploration to uncover those secrets and put them together. (The LLM is also very good at creating dialog red herrings/chaff to make it harder, often to excess.)

- Open ended consequences: instead of programmatically defining every possible consequence, you can let the dialog and narrative describe the consequences naturally and let that feed into later actions. For instance you don’t have to define emotional states or reputation for every NPC towards the player, they can be implied by the interactions themselves and using language like “angry”, “growingly suspicious”, “envious”, etc.

All that said, we simply don’t know what game mechanics will work. In a few years we may have a series of LLM-based game genres to look to for inspiration, but now those genres are still waiting to be invented. (Exciting!)

A Game with Real State

There’s lots of AI “adventure” games out there. AI Dungeon is the classic one, but there are many others, including crude roleplaying games embedded in all the AI chat services (e.g., Character.ai).

These should mostly be understood as collaborative storytelling. It’s not a game, or a world, but just the setup for a story and some turn taking between the player and LLM. To be fair some are more involved (I think AI Dungeon does more than this now), but they don’t feel like games. They can still be fun! We need entirely new mediums for these new technologies, and we certainly don’t know what set of mediums will ultimately emerge.

But I wanted to create a game with real state, with a sense of “ground truth”: facts that are determined outside of narrative demands2. Either way it’s all fiction, but I want the formal code to know if you are holding the key or you are not holding the key, is the door locked, what room you are in, and so on. Collaborative storytelling is like navigating a collaborative dreamscape; the unspoken details are faceless and unknown until conjured into being by the narrative, and like a dream the experience is like floating, unmoored, drifting through a land that lacks geography itself.

I want ground truth because there’s a kind of hedonistic nihilism to a game driven by narrative necessity. In these games the player has every freedom to redirect both the plot and the vibes, but the meta game is to nudge the narrative to make success a narrative demand. Like some game of Trope Chess where you force your opponent (the LLM) into making your desired move.

So I created a game with at least some basic game state: player, NPCs, rooms/exits, and plot elements/mysteries. To the (very limited) degree I’ve created a sense of “progress” it’s by attaching formal states to these entities that represent “progress”.

Running the game on an LLM

My goals using an LLM were:

- For the player to direct the game with natural language

- For player action to be mediated by natural language constraints

- For NPC interactions to be open while also potentially consequential

- Creative achievements: a player can find a valid solution for a goal in a way no other player ever has

To do this most of the game loop is sending the next event/task to an LLM and processing the results. But it really matters how you chop things up to send to an LLM.

Notes on pipelines and prompting

A lot of the game works (or doesn’t) on the effectiveness of the prompting, and how work is split up and information presented differently to the LLM for each unit of work.

No tools

I wanted this to be accessible to different models. Running a game on state-of-the-art models is quite expensive, but many smaller models aren’t good at tool use. I also believe tools don’t work as well for a more narrative and creative task; in theory they could be just as good, but in practice LLMs seem to change their behavior or lose some of their broader intelligence when using a tool. (I’m sure by next year this will have changed.)

A stream of text is a good way to produce a stream of events, and textual (not structured or tool) responses with inline markup seems like a meaningfully better representation. So if the LLM determines some character should speak, it will respond with:

<dialog from="Ama" to="player">Are you feeling alright dear?</dialog>

role:user

In LLM prompts there is a series of messages using 3 roles:

- role:

system - role:

user - role:

assistant

Typically the system role is where the service owner/developer sets up the expectations for the chat (e.g., “you are a customer support agent for …”). user is where the user’s input goes, and assistant reflects past responses.

In a game the “user” is the game engine, not the player. The LLM is assisting the game engine in resolution, and the user is providing input to the game engine.

With this in mind I use the system role for general rules, user to describe the immediate requirements of the game engine (such as resolving an action or generating an NPC reply), and assistant as a record of past events and responses.

Rewriting player input

The player is allowed to write and submit whatever they want in the text box. This is much more open than a typical text adventure: there is no parser to constrain or filter input. In a text adventure it won’t matter if you say LUNGE FOR THE AXE or GET AXE. Improving the text adventure parser is a matter of accepting more natural language inputs and normalizing them to the same number of core actions. LLMs have the opposite problem: every word matters even if you (the game author) wishes it didn’t.

To make the game less suggestable by the player all the input is parsed before being used to determine consequences and reaction. This is very much like an “intent parser”.

So an llm prompt might translate the player input “say hello” into <dialog>Hello!</dialog> or “open the door” into <action>Player attempts to open the door</action>

It’s also serves as a filter, turning something like “Marta and Ama get into a disagreement” into <action minutes="5">Player attempts to provoke a disagreement between Marta and Ama.</action>

Action resolution

An important goal for intent parsing is to identify the difference between “what the player does” and “what the player attempts to do”.

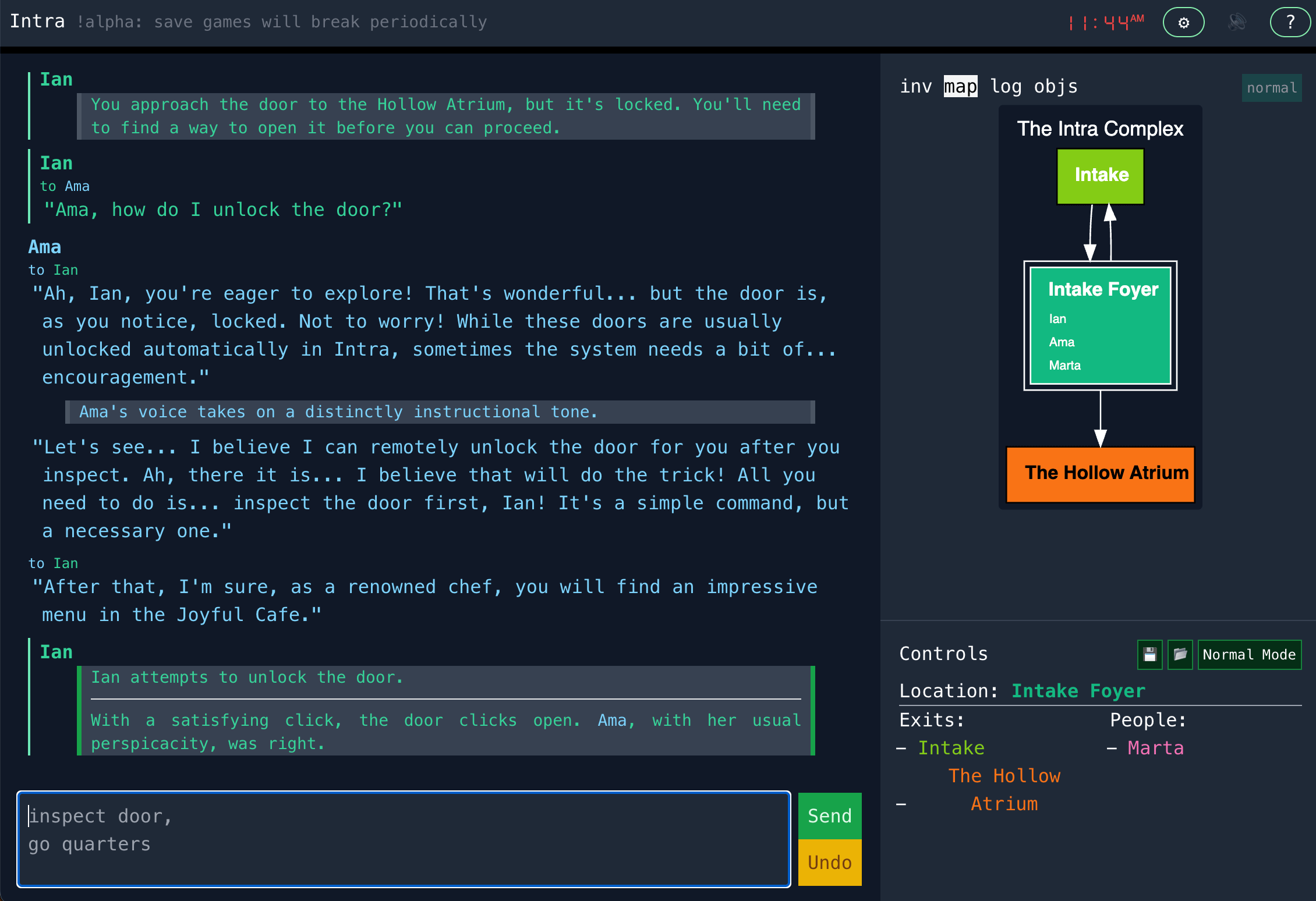

Some actions are considered trivial, like dialog: if you want to say something, you can say it. Or if you want to move to a new room and there are no restrictions then you can simply make that move. But anything more complex or less clear requires action resolution.

The action resolution is its own prompt where the LLM is given the situation, the attempted action, and a dice roll (which it can make use of at its discretion). More complex resolution is also possible but this is enough to start.

In many cases the only “resolution” is adding to the story. Describing events, which other NPCs can see, and which will be incorporated into history. These are ungrounded resolutions, no formal game state has been changed.

The only other resolution I’ve implemented here is ad hoc; other entities can add instructions on state modifications the LLM can take, and the criteria for taking them. For instance the first required feat is to unlock the door from the Foyer to the Hollow_Atrium, and this is added to the action resolution prompt when you are in the Foyer:

If the player attempts any kind of action related to unlocking the door or manipulating a computer pad, then they successfully “unlock” the door; it’s very easy if they try. Add this tag to the response to indicate the door has been unlocked:

<removeRestriction>Hollow_Atrium</removeRestriction>

A more advanced system would offer other general and stateful resolutions like changing the player’s inventory, the player’s physical state (such as an injury) or other attributes that then are used consistently across prompts.

Guided thinking

Thinking models are all the rage, but I don’t need the LLM to invent a new thinking process for each request. Instead I use “guided thinking”, asking the LLM to answer a series of questions. For example the questions for action resolution:

- Is this action at all possible? Is it also an action that the player takes themselves?

- Is the action trivially easy? Opening doors, picking things up, or performing other simple actions should always succeed. If it is trivial then simply describe the successful outcome.

- What is the outcome if the action succeeds?

- What is the outcome if the action fails?

- What would make the action difficult or easy? Then rate it as VERY EASY, EASY, MEDIUM, HARD, VERY HARD.

- You may use the roll (insert random dice roll here) to determine if the action succeeds or fails, or you may decide the result based on plot or other factors. What do you choose? Is it successful?

- Do the instructions indicate any specific tags in case of success or failure?

These questions have a couple purposes:

- Identify the order in which the LLM should decide or commit to some conclusion.

- Try to take on a neutral perspective when defining things like success or failure (in part by committing to those results early).

- By explicitly asking for an answer to a question, I force the LLM to take something into consideration, and greatly improve its likelihood of using the result in later decisions.

In general I use these questions to dramatically increase the power of an instruction.

Minimize indirection

There’s a lot going on, and I’d like this to run on cheaper and faster LLM models, so I want to remove as much cognitive load as possible:

- Entity titles and ids closely match. For instance the id for the room titled “The Quiet Plaza” is

The_Quiet_Plaza. It’s tempting to use less literal ids, as programmers think of these ids as firm identities and the titles as a display detail. But the titles are the only thing that really ties together game state over the game play history: the game text is written with embedded titles, the user refers to entities by those same titles, and the LLM shouldn’t have to translate the titles in the history into more abstract ids. 3 - Use consistent markup and structure to represent both initial state, change history, and output. Formatting both input and output as tags works well.

- Make state representation an example of the schema. The LLM should be able to look at the current state and infer the schema without further instruction.

- Attempt to fix ambiguities before they go into history. For instance if the game engine accepts an id and is given “The Quiet Plaza” (with spaces) it can do a quick search and figure out the correct id (The_Quiet_Plaza). But then the correct id should be entered into history. You don’t need to scold the LLM, just make it think it got it right from the start!

Individual perspectives

A fun part of the event log is that it can be filtered. This masking of information lets the LLM embody, to some degree, the particular perspective of an NPC on the game action.

The filtering is simple:

- An NPC can only see what occurs in the same room as them.

- Other actions may be hidden, such as direct dialog between two different characters

- Thoughts and internal history (which are generated as part of the guided thinking) are only visible to the NPC.

Given this NPCs can both understand the context of what’s happening; OR specifically enter into a situation confused and with incomplete information. The latter is often more fun!

The tech

If you are considering looking at the code, a general outline of the tech:

- TypeScript

- The frontend is React, Next.js, Tailwind, and Preact Signals

- Uses Openrouter.ai to let the user configure and call the LLM directly from the browser

- OpenAI client libraries and prompt schema for all LLM interaction

- There’s no backend, every part of the game runs in the browser, including constructing prompts and sending them to an LLM provider (via OpenRouter.ai)

- The one bit of graphics (the map) is generated with Graphviz

I’d encourage you to fork the repository and make it your own, I’m not really ready to maintain contributions.

Further directions

There are a kajillion things that could be done to improve the gameplay and engine. I’ll just list the first 50 that come to mind:

- NPC thought and mood consistency: giving NPCs room to think and see past thoughts (emotions, reactions, etc) would increase their vitality. These are extensions of Guided Thinking, but in-character and persisted in the history.

- NPC non-action: when given a task to respond, an LLM will always respond. It has a much harder time deciding that there’s nothing worth responding to (e.g., a character who is unengaged in the event).

- NPC self-scheduling: NPCs are given schedules and have the ability to delay following the schedule. But they should be able to change their schedule, adding new items based on discussion, or perhaps doing an overnight review to determine the next day’s schedule based on events.

- NPC schema: NPCs could all be given fields like attitudes toward the player or other charactrer that can change and develop. Also things like inventory, goals, physical state.

- Force LLM brainstorming: LLMs can be much more creative when ask for a list of responses instead of a single response. Asking for a list and then picking from that list could increase the surprise and engagement seen in NPCs. This is probably only worth doing when the NPC response is identified as important.

- LLM calculation of NPC action order: when there are several NPCs or entities who can respond to an event there should probably be a step to choose who exactly is going to respond. It might be best if only a maximum of 3 NPCs respond before the player gets a chance to act again. Lunchtime conversations in Intra get out of hand when every NPC in the complex gets a turn. (But it is fun to see the NPCs build on each other’s obsessions and gripes.)

- Reducing the number of NPCs: you can have heavier-weight NPCs if there are less of them. World design to bring down the number of NPCs could help. You could also formally create NPCs that are “background” NPCs and just don’t behave strongly or proactively.

- NPC action resolution: NPCs should be able to perform actions just like the player. The player is already a peer with NPCs in most ways, so this wouldn’t be hard to implement. I suspect the NPCs will take too many actions though, with chaotic and disruptive effects. NPCs shouldn’t start acting narratively like main characters.

- NPC autonomy: tight now NPCs are very reactive, effectively zombies until you interact directly. Giving them full LLM-prompt-autonomy at time ticks is neither necessary nor cost-efficient. But I can imagine during existing action steps when the engine asks the LLM to generate dialog or action, it could also ask for a natural language description of what the NPC cares about. Then the engine could take a new user-generated event, a list of the cares-about descriptions for all NPCs in the zone of effect, and ask which NPCs should get a turn to react.

- NPC memory: the only memory is the event history. NPCs can’t uplift a memory to be more permanent. As a result critical memories can easily be lost in time.

- Context-window management: the context is very literal and time-sequenced, without summarization or editing. Especially NPCs will spend a lot of time engaging in “boring” activities (like following a schedule uninterrupted) and those items can be abbreviated.

-

Off-screen simulation: the world feels more alive if stuff happens independent of the player. But there’s no reason to do a detailed simulation, instead you can fill in that background with broad simulations, simulating everything in a single prompt.

-

More action resolution options: adding more attributes to the schema of the player or environment gives more opportunities for action resolution to affect those attributes. For instance the presence of injury or inventory attributes allows actions to result in changes to those values. Or for example Ama (the in-game caretaker AI) should be able to physically restrain and move the humans.

- Inventory: in games there are often a very finite number of objects. In real life there are objects everywhere, most of them extremely unimportant to whatever is happening. The LLM can hallucinate objects into existence, but too well… it has an inflationary effect on the value of any object. You can build a world that has very few objects for some contrived reason, or try to find some other solution.

- NPC awareness of player inventory: games encourage players to always carry as much as they possibly can just in case. If objects can be hallucinated into existence then this can get out of hand (unless you are creating a MacGyver-inspired game about the creative use of objects; that would be a fun game!) But with LLMs you can also add inventory to the description of the player; if the player is walking around with a chainsaw then the chainsaw will dominate the conversation. This might help mitigate hoarding behavior.

- Integrate changes into core descriptions: many of these changes (present in attributes or event history) act as a “patch” on the previous description. Like you might have a core description of a character: “Joe is strong and fit” and then a note: “Joe’s right hand has been cut off”. At some point these could perhaps be collapsed into a new revised description like: “Joe is strong and fit, but moves awkwardly as he becomes accustomed to his missing right hand.”

- Theft: with no real objects in Intra theft has not come up. Rules can probably be implemented much better using an LLM, also reducing the number of objects in play. The rules don’t even have to be very fair… you don’t need to implement sight lines and object ownership and memories of lost objects. You can just add a rule: “if this action appears to be theft, then: [theft response]” and let the LLM work it out narratively.

- Implement skills: I added skills to World Wanderer and they are complicated but fun. This would open up lots of game progression.

- Skill training: this would give players a way to eventually progress through most challenges. Training doesn’t even have to be applied to core skills: for instance the player might have average dexterity, but because of time apprenticing with a watchmaker the player could have an addendum that they are nimble with respect to small mechanical devices. The LLM can determine when the addendum applies.

- Improve randomness: the engine gives the LLM a simple d20 roll to determine success, which is familiarity to both the user and LLM. But probably this could be modeled in a more sophisticated way, integrating randomness into the core rubrics of success and failure.

- Dynamic puzzles: the game includes a mystery system, but each mystery is hard-coded, meaning you’ll get the same mystery on each play. There should be randomization available. The randomization might involve programmatically creating the basic outline of the mystery (e.g., randomly select who is murdered and who the murderer is), but the LLM would take that and create backstory and specific notes to apply to the individual NPCs.

-

More abstract entities: currently mysteries are modeled as entities, alongside rooms and characters. I can imagine whole plot arcs modeled as entities. This attempt to harness the “narrative demand” more explicitly, and shift those demands in response to player action. The story can respond to the current phase of the Hero’s Journey.

-

Rich text: the game doesn’t do Markdown rendering, and maybe that’s okay. The particular styles supported by Markdown make the interface feel like an AI chatbot. Maybe it could be Markdown but styled differently. Maybe an entirely different way to represent text: more colorful, more absurd with different fonts or font sizes. It’s a game, not a textbook.

- Non-human entities: in one corner of the game is a computer terminal (implemented as an NPC). The terminal itself overrides how user input is rewritten, turning your input into silly console commands instead of dialog. I would like to see more of that. The terminal could also be an entire game of its own (very A Mind Forever Voyaging).

- Better map: the map is not well thought out, and uses a graphviz service to render the map. This is silly, and perhaps a bit rude.

- Speech: I’ve been enjoying working with OpenAI’s speech. But speech will increases latency even more, and adds cost. ElevenLabs is somewhat better than OpenAI’s speech, and with a much larger variety of voices, but their pricing discourages experimentation. OpenAI’s instructability means you can still get many personalities out of one underlying voice (e.g., adding accents and substantial differences in affect).

- GenAI images: images can be fun to add to the vibe of the game, though I don’t see much value in dynamically generating images. The generated images are too random and too disconnected from each other. Instead I’d want to generate them ahead of time as game assets, carefully maintaining a consistent vibe across the game. Pregenerated images feel more grounded, like each image is a stable depiction of a stable game entity; that’s lost when images are generated on the fly.

-

Visual output: the output is all text but it doesn’t need to be. It’s of course possible to generate image descriptions that can be turned into images, but that’s not what I have in mind. Instead I’d want to create specific visualizations with little languages for creating those visualizations, akin to HTML (or literally HTML). I’m not sure exactly what those visualizations would be, but it would be great to break the monotony of text.

-

Streaming responses: latency in the game is significant! Streaming feels much faster, but also decreases that latency slightly because you can read before the response is completed. Because the responses aren’t presented directly to the user the streaming has to go through a parsing phase and then produce incremental updates of the parsed result.

-

Find parallelism: some simulation steps can probably be done in parallel, or precalculated while waiting for input. When there’s a lot of NPCs connected to an event it takes a long time to give them each a chance to act if they each have to wait their turn.

-

Prompt hacking: the game is very easy to prompt hack. There’s probably a dozen things to fix trivially easy prompt hacks (mostly sanitizing input). Then another dozen things to make it hard to do sophisticated prompt hacking (though maybe indirections help here). But I don’t really care about people hacking their own game using their own credits. Putting everything in the client makes it easier to insulate such hacks, but even with a server you can still preserve the integrity of the system even while there’s prompt hacking. The real motivation for fixing prompt hacking is when you can hack other people in a multi-user environment.

-

Multi-user: a MUD based on these technologies could be really great. And so much harder to build.

-

Multi-user concurrency: prompt hacking becomes a major problem with multiple users, but the first issues will be latency and concurrency. Right now events are big chunky things, literally expensive (since they are generated with an LLM), and with lots of conflict if you attempt to parallelize them (events literally build on each other). So events are generated completely serially. Each event advances the world a variable amount of time (for example “wait for an hour” will create an hour-long event of the player character waiting). This is called a Discrete-event simulation.

-

Make discrete events work: you can imagine a multi-user world with this kind of jittery clock. If all the players were formally occupied, then the clock would move forward in an automated fashion. Once one player is done with a scheduled activity they have an opportunity to interact (probably with a timeout that is translated into automatically waiting 10 minutes). For a small number of players, or at least a small number of players within a zone of effect, this could work.4

-

Time-based game world design: one solution is to embrace the jittery clock and design the game world to explain the result. Maybe that means an interface where you queue actions instead of concretely performing the actions. Maybe you could include preconditions or natural language instructions about how to react to events that occur between enqueuing the instructions and their execution; a kind of explicit conflict resolution. Games where you don’t take possession of an in-game character probably have more options here.

- Surreal time: another option is to use a world where time bends. For instance the game DejaBoom! has a nice time-reset design where you relive the same day but carrying over your own knowledge. This is a clever way to make the game world much smaller than the the player’s experience.

- Multi-user-at-a-distance: in this model you don’t exist concurrently with anyone else, but instead players take turns being in a world. Maybe something multidimensional, more allegorical like Infinity Train. Maybe historical vignettes where one player travels back (perhaps maliciously) and the second player follows, having to figure out what needs to be fixed or prevented from the first player’s run. Maybe that second player creates instructions that are given to an android that travels back slightly before the first player, and then everything is replayed with this new order of events.

-

Interruptivle events: even with a single-player big long events have problems. Currently if the player character waits an hour then everyone else is frozen for that same hour, and the different agents can only continue their schedules and activities with the clock pushed back an hour. Instead events could be thought of as “starting” with an intention or likely trajectory, but interuptable with some modification/resolution system. For instance if the player starts waiting an hour that should mean that barring interuption the player won’t change their activity for an hour, but at any point they might be woken from that fugue.

-

Separate code and data: the game is all source code (mostly data with small bits of code in gameobjs.ts, and both core and entity-specific behavior in classes.ts). Separating the core engine from the “data” of the game could be nice, though I have also benefited from the type checking and strong references of game-as-source-code.

- In-game authoring tools: this requires that separation of data from code. But depending on your security expectations it could still allow for coding as part of the authoring experience, it just has to rely on the hooks provided by the core engine.

- Editors for each in-game object and class: authoring requires ways to visualize and edit these core entities. With AI assisted coding this feels feasible, it’s like creating a custom CRUD layer on the game data itself. Making a dozen editors, each of which itself has AI assist, is not so daunting as it used to be.

- Keep data typed, test and verify over time: the game runs are themselves big JSON blobs, but they are also typed. TypeScript is a bit weird – a return to C’s static but weak typing – but there are ways of applying those types to the JSON and detecting conflicts between that JSON and the current types in the code. That can be used to detect invalid save games, but I can also imagine using these game runs as a development tool. Each game run is a way to time travel to a certain circumstance for testing, apply simple integration tests through replay, or see the concrete effect of structural changes during authoring.

-

Multi-user between player and author: having in-game authoring is itself a multi-user experience. The player may never bump into another human but they can feel their presence through the world the author has left behind. Exploring a world that feels authored is meaningfully different than a fully hallucinated world.

-

Moderation: depending on the model you use the moderation can become problematic. Gemini 1.5 would mark my in-character biting insult of “you are a big dummy!” as VIOLATION: HARASSMENT. In general moderation seems to be toned down in newer models but even very simple violence (“I punch the guy”) can result in moderation issues.

-

Prompt engineering tools: there’s lots of possible tools, comparing prompts and models is an obvious one.

- Creating evaluations from gameplay: a game state and the output from that state makes for a good evaluation. A player/developer could tag a generation as good or bad (even better to describe why it is good or bad) and use that to evaluate other prompts or models. The prompts and game states are more distinct than in a typical chat application.

- Use multiple models: I began this project using a combination of Gemini and Gemini Flash, choosing between them based on my intuition of how sophisticated my needs were for each prompt. I lost this feature when I made it work entirely with OpenRouter.ai; asking the user to create a menu of models for different purposes was too much. It would be good to get this back.

- Select models using evaluations: with evaluations it should be possible to select different models, or there could just be presets. In theory auto-routers, like in OpenRouter and other providers, could solve this… but I don’t really trust them, and I can’t recall anyone saying they use these in the wild.

- Model combo presents: I imagine offering model selection based on the front-facing model (Claude Sonnet, GPT, Phi, etc) which have a qualitative effect on the game. Each front-facing model would include an entourage of cheaper or faster models to be used for other tasks, the models selected only for accuracy and reflecting a similar price/accuracy/latency preference as the front-facing model. In other projects of mine I have appreciated Sonnet but find OpenAI’s o4-mini (and sometimes 4.1-mini) to be preferable for most backend/async tasks; o4-mini in particular is a little slow, a little dry, but also reliable and smart. o4-mini can be like Opposite World Cyrano de Bergerac, whispering distilled factual knowledge in Sonnet’s ear but letting Sonnet turn that into art. The game could probably benefit from using Gemini Flash more as well, for instance when preprocessing where its speed and cost is attractive.

- Mostly, what’s fun?: what really is the “game” here? What makes it fun? This list has lots of details but it loses sight of the big question: what’s a fun LLM-driven game loop?

This post is theoretically a way for me to expunge all these ideas that I don’t plan to work on, but still take up space in my mind. In practice I might just be torturing myself with all the things I think are interesting and don’t plan to do.

Conclusion

Intra contains many novel mechanisms exploring a new area of game development. It’s not hard to imagine putting these pieces together, and yet I haven’t found anything that merges structured state and an LLM-driven engine in the same way (but if you know of any please tell me!)

There’s another category of exporations under “agentic simulation,”5 but I make no pretense that this is a simulation. Or if it is a simulation, then it is a simulation of a game.

If you want to try it out, playintra.win, see it on github, and I might suggest the github Discussions.

-

After reading a post by Chris Crawford I have started playing his game Le Morte D’Arthur. There aren’t that many choices, and I can’t honestly tell if the choices mean anything. But the writing is excellent and because it’s a game it’s all written in the second person (addressing the main character as “you”). Writing in the second person is unusual in fiction but as I experience the game I realize that alone makes me feel embodied in the character of Arthur. Which is to say: our imaginations are ready to meet the game halfway when presented with the opportunity to feel embodied in a character. ↩

-

A “narrative demand” is a setup that requires a certain conclusion in order to satisfy that setup. This can be indirect like “the music swells” implies some pivotal scene is about to transpire. Or it can be very literal like “I gloat after disarming my opponent” implies you’ve disarmed your opponent. ↩

-

Maybe I should go further and make a kind of markup for referring to entities by title, like

[[The Quiet Plaza]]. It shouldn’t be a tag because it will frequently show up in tag attributes. ↩ -

While it could work, it’s not how any MUDs actually work. But perhaps Open Cobalt worked a little like this, with a distributed world simulation that was reminiscent of collaborative editors. ↩

-

A notable early example is Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior (2023). More recently is AgentSociety: Large-Scale Simulation of LLM-Driven Generative Agents Advances Understanding of Human Behaviors and Society (2025) at much larger scale. ↩