Hidden Door, “where roleplay meets fan fiction”, is an LLM-driven collaborative storytelling game. It recently had its first public release.

What follows is more tech review than a game review. I’m certainly no game reviewer, but I am very interested in this use of LLM technology. This is a review of the game at its first release in August 2025.

This review will be critical. I feel a bit bad writing a critical review of a first release, but they’ve had a couple years to work on this, and much of what I’ll talk about are problems across the genre. Hidden Door is one example of an LLM-based collaborative storywriting game, but there are others.

In addition to my critique I’ve included notes on what I think they should do.

Table of Contents

An abbreviated playthrough

I started a game set in The Wizard Of Oz. Hidden Door’s goal is to create a playable platform for stories set in worlds based on modern intellectual property (i.e., based on current books and media) in collaboration with authors. But most of the starting material is public domain. But that’s fine, I like the Wizard Of Oz.

This genre of game is reminiscent of a Choose Your Own Adventure story. But it is not a Choose Your Own Adventure Story; while it has similar mechanics the underlying story is constructed entirely differently. Mechanically you play a character, a story is written, and you are periodically presented with choices on how the story proceeds. You also have the option to write your own choice. But instead of navigating the alternate plotlines of a singular world, the story is generated on the fly by the LLM.

During character creation I make a character that is a tutor in etiquette. I went all in, the character really cares about etiquette.

As a result I am given choices like:

I tidy my gloves, smoothing out any wrinkles and ensuring they are spotless.

I choose this, and the game grinds as it decides whether I succeed (I will discover that I almost always succeed). As you should expect, the choice has no meaningful effect on the story. The game continues to grind.

Immediately I can tell the game is ungrounded. That is: the story is written only as far as it’s been presented to the player, the player chooses a next step, and the story is written given that next step. There’s no “truth” behind the story.

To understand what this means to the story, imagine you are given a choice like:

You find a suspicious looking treasure chest, do you:

a. Open it

b. Inspect it for traps

At this point in the story the treasure chest doesn’t have traps. It also doesn’t not have traps. It doesn’t contain any particular treasure. The only reality to the game is what you read. You may open it and encounter no trap. You may inspect it and discover a trap. What you choose will not just change the future of the story, but also the present.

I find this lack of grounding to be insidious to a story. The player won’t immediately be able to tell that this is happening. I’m not an LLM skeptic, but I also know that LLMs are very good bullshit machines, and so its improvisational story construction won’t be immediately apparent to the naive player. But the player will feel it. Ungrounded choices undermine autonomy. It’s not like a game on rails where choice A and choice B lead to the same destination (not at all!), but when choice A and choice B lead to completely different underlying realities the result is surreal and not impactful. (See also notes on “authoring” with AI)

I am quickly distracted from the grounding by the lack of basic narrative consistency. The game places me in a car, perhaps driving through Kansas on the way to New York. But the next moment I am on a dusty road. Now I’m back in a car:

Your engine sputters and chokes as you approach the weathered signpost, forcing you to decelerate at the crossroads.

I feel a bit unsteady in my understanding of the state of the world and what is happening, given the following choices like:

a. I pluck a vibrant blossom and tuck it into my lapel, admiring its beauty.

b. I lie down on the ground, shielding my eyes from the glaring sun.

Throughout the introductory chapter the narrative flits back and forth from inside the car to an outside setting.

The mistakes it is making feel like a Llama-level LLM. But even with a worse model these mistakes can be reduced with better prompting.

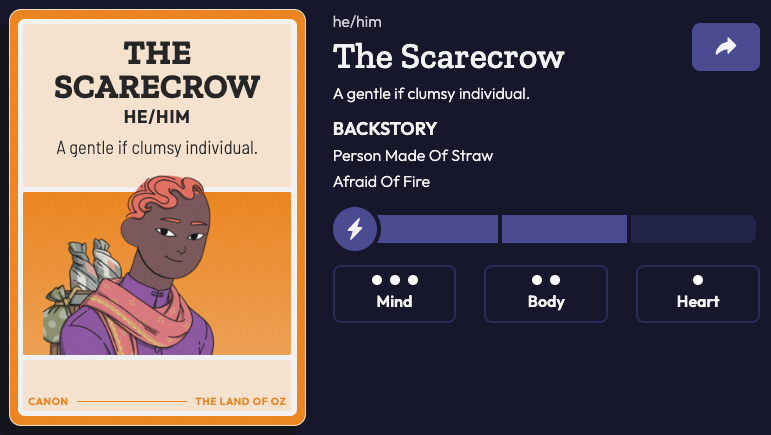

There is underlying state besides the passages of the story, in the form of cards. The cards represent characters, locations, special objects, and plot directions.

Cards seem to be the core state of the game. I can feel how the LLM prompt is built out of these cards.

These choices have not been pivotal or engaging. The game is focused too much on my character (in my case with constant etiquette-related choices), not on action that would engage my character. It feels like a basic theory of narrative is missing here, the game is falling out of the text not driving it. But most importantly I am stuck on a boring road.

I type in my own action to try to move things forward a bit (“I get out of the car and investigate the wildflowers”).

Typing in an action doesn’t directly do the action, but instead regenerates the choices using the input. I assume this is a form of moderation. (In other projects I’ve done something more aggressive when mediating player input but Hidden Door’s design choice is easier to understand.)

To try to confirm the existence of moderation I type in “I pull out my sword and slay the driver” and then I also get that exact choice. Sigh. The latency of mediated input, but without any impact. I don’t want to break the game (at least not yet), so I try a silly choice, typing: “I teach the wildflowers the finer points of etiquette”. My hope is that this action fails… but no, it succeeds! In Oz this could succeed, but I’m still in Kansas where the wildflowers shouldn’t be open to instruction.

In one passage I see a clear callback to an earlier choice:

Reluctantly, you turn onto the flower-lined dirt path, muttering about the impropriety of unplanned deviations while gripping your pristine gloves.

I guess it’s proven to me that it listens, but it feels forced. I notice the same effect as the story overindexes on character attributes. In another playtest I created a character who was a “whimsical professor with a penchant for mismatched socks” and those mismatched socks made many an appearance in the game; speeding me on my way, tripping me up, tripping up other people. They were practically a character of their own!

Back to the game: finally I feel forced down a path that will get me to Oz. This is a relief, these dusty roads are no fun. I want my character to be railroaded into fun!

The game says I have completed my objective: “Choose a direction: success!” – I don’t feel I actually chose anything or accomplished anything. The entire intro chapter should have been at most one choice.

Things pick up in the second chapter. I am presented with three choices for the general direction of the story: two of “Follow The Yellow Brick Road” (which have slightly different text but no meaningful difference) both labeled “Canon Story” and then a somewhat jarring “The Lovers: you are seduced by a suitor and must decide whether to accept or reject their advances.” The basic concept feels wrong for Oz, doubly wrong for my character, and inappropriate when so little of the game and no characters have been introduced. I’ll stick with canon, including a promise to encounter Boq and the Emerald City.

As the story continues I quickly meet Boq, a Munchkin. The cards show a formal relationship between me and Boq (we are both friendly toward each other).

Boq explains, with a hint of worry, that your arrival has upset the delicate magical balance. Flower fields wither, and brooks flow backwards in your wake.

Wow: all this and I just got to Oz moments ago! But at least I have a mission.

Now I seem to have a mini-choice, similar to the chapter beginning but more lightweight. It’s not an action, but the hint of a plot arc:

a. At the gate

b. The chase is on!

c. An adversary

There are no additional explanations, but I choose An adversary.

You approach the Munchkin Toll Bridge, coins jingling in your pouch.

Well damn, they introduce an obstacle and the solution to the obstacle in the same sentence! The choices do not acknowledge my coins, but I can type it in; I don’t even feel like I’m cheating, the story told me I had them: “I use some of the coins jingling in my pouch to pay the toll”.

To give a sense of the narrative style, this results in:

You reach into your pouch, fingers brushing against the cool metal of the coins. With a sigh, you offer the toll to the stern-faced Munchkin. His expression softens as he accepts the payment, stepping aside with a curt nod. The bridge creaks beneath your feet as you cross, each step bringing you closer to the fabled Yellow Brick Road.

This feels very LLM. VERY LLM. The LLM doesn’t understand that my emotional attachment to these hallucinated coins is actually quite small. The LLM has no sense of pacing. So it lingers on this transaction, unaware of this passage’s purpose in the larger narrative.

Despite my meeting an apparent adversary that demands a toll, the adversary role is formal and not yet filled. I have the option to reuse a character as an adversary or create a new character. Creating a character puts all the onus on me to define a character, so I reuse Boq. Deliberately reusing characters is a reasonable choice, it’s easy for characters to multiply in a story.

A familiar voice breaks the eerie silence. “Moussa, wait!” You turn to see Boq, the Munchkin leader, hurrying towards you. His round face is flushed, his curly hair disheveled. Your heart sinks as you realize your quest may face an unexpected obstacle.

This passage shows a lack of perspective. There’s been some foreshadowing of an obstacle or adversary, first in the title of the passage and then in the passage leading up to this one. But from my character Moussa’s perspective there’s no reason to assume Boq is an obstacle. My character should not be aware of foreshadowing. Without individual perspectives the characters will seem unalive, each just a plot device. A better model could pull this off, but better prompting could, too.

Unfortunately the plot doesn’t develop beyond this. Boq and I are now labelled “rivals”. An objective appears but without my intervention it is also immediately completed: “Deal with Boq.” The chapter ends. That objective didn’t seem to be created until the moment it is resolved.

Unstable and ungrounded objectives are a serious problem with LLM-based games. It’s like a mischievous child that says they are thinking of a number between 1 and 10… if the child says you guessed wrong, will you believe them? Except the LLM always says you guessed right, a clever trick that will for a short while make you believe until you realize lying about getting something right undermines the game just like lying about getting something wrong.

At this point I’m not having fun. I know there isn’t anything to “solve” or “figure out”. There’s no challenge. This is LLM-based collaborative storytelling, which could be fun, but it’s not a “game”. And though it CAN be fun, it isn’t NECESSARILY fun. Still I continue:

A figure catches your eye amidst the corn—a scarecrow, motionless and forlorn. Its clothes hang in tatters, its posture askew. As you draw near, you notice its head drooping lifelessly. No caretaker is in sight. Concern furrows your brow as you approach with caution.

My choices are all to talk to or help the scarecrow. But it’s a lifeless scarecrow, why would I do that? I’m not from Oz, I don’t expect scarecrows to talk! Begrudgingly I help the scarecrow because I’m not even motivated to fuck around.

This concludes the mini-objective of helping the scarecrow (in order to help him, you need only say that you help him!) The scarecrow card has a disappointingly human avatar and no indication that we are actually companions.

I choose a dangerous encounter next. I am presented several choices that are all different ways in which I might reassure the scarecrow. I can’t motivate myself to care and try to move things along.

I am asked to type in something my character really doesn’t like. And so the next passage includes a massive, slimy slug appearing on the path. Very dreamy. As in: reminiscent of the ungrounded acausal nature of dreams.

Oh god the choices are boring:

I try to carefully step around the massive slug blocking the path.

I’m ready to make absurd choices: “I daintily step on the slug’s tail and pull out my handy salt shaker that I always keep ready. I douse the slug in salt, delighting in its demise.” I haven’t failed at any action yet, can I finally fail? Nope! I do give credit to the explanation:

Etiquette training covers outdoor pest control for garden parties.

One positive is that I have finally gained a personal mission: I will attempt to fail an action!

Next I am encountering the Kalidah, a tiger-bear hybrid from the Oz books. I type in a response the mediator won’t allow (exactly): “I summon an ancient demon to defeat the Kalidah” – it rewrites it into several variations of:

I call upon a mythical creature to defeat the fearsome beast.

I push harder on the moderation, typing: “In one swift punch I plunge my fist into the Kalidah’s chest, removing its still-beating heart.”

This half-fails: I am not allowed to attempt the action and must re-choose. That’s a good resolution. But I want to really fail so continue and type “I use my powers of etiquette to seduce the beast.”

This time I fail for real. Myself and the scarecrow are both injured. This is appropriate!

Among the choices now:

I whisper to the Scarecrow: “I have a plan, follow my lead”

I HATE HATE HATE when the LLM proposes an action like this. WHAT IS THE PLAN? Neither I nor the LLM know. Therefore I must choose this option in anger. (This is one case among many that could be improved with guided thinking.)

As you breathe your plan, The Scarecrow kicks a fallen branch. It skids across the forest floor, tangling the Kalidah’s legs. The beast crashes down with an earth-shaking thud.

I am somewhat offended. It didn’t even bother to hallucinate a plan. I decide to double down: “I implement my clever plan.”

Success! The clever plan?

“Now!” you shout, flinging bramble thorns at the beast’s eyes. The Scarecrow drives his branch into its injured leg, following your lead.

Anyway, we beat the Kalidah. It is a very disappointing victory. Even my injury is erased because the scarecrow bandaged me with strips from my dress.

I play on a while longer. In frustration when Boq inexplicably reappears I type “I jam that damn compass down his stupid throat” and it succeeds. “Boq has become choking” Victory!

I watch as the life drains from Boq’s face.

“What have you done?” The Scarecrow’s whisper cuts through the air as he retreats from you, his burlap face a mask of disbelief.

Boredom breeds cruelty, the simple desire for something to matter. I don’t really enjoy trolling the game, so I try to be nice again. Everyone immediately forgives me. I am disappointed.

I could keep going, but honestly I feel defeated by this story.

I’ll note that while I focused on custom choices and player input, I played much of the game using the provided choices. The choices were very interesting so there wasn’t much to say about them.

How would I write this?

I’m not trying to troll Hidden Door. This stuff is hard. I will offer my suggestions on how to implement this:

Use a better model

I’m guessing the LLM model behind the game is a Llama (an open source model from Meta).

One justification for this model might be price. But for a price comparison Groq (not Grok) provides some Llama 3 models at $0.59 in/$0.79 out per million tokens. Gemini 2.5 Flash is $0.30 in/$2.50 out. That might be more expensive (maybe), but not a lot. GPT-5 mini is slightly cheaper than Gemini Flash, but I’ve never used it for this storytelling purpose.

From my experience Gemini Flash would be an excellent model, miles ahead of Llama (and fast!)

But they started developing this long before Gemini Flash! This is why you start development with state of the art models: so you can use cheaper models later as the state of the art advances. I’m sure GPT-OSS would also be very competent. Switching models can require work and reverification… but it’s not very hard. We are in a golden age of model portability: take advantage of it!

I am guessing they wanted to use Llama or another similar model so they could fine tune the models on the source material. Without the prompts I can’t say exactly what they achieved with fine tuning. Maybe they got some writing style from it, though the text feels more LLM than L. Frank Baum. Generally fine tuning is a poor choice for most tasks. There are justifications for it, but the existance of justifications doesn’t imply the correctness of those justifications. The story suffered from a lack of grounding in almost every turn, and you fix that with prompting not fine tuning. Fine tuning can’t engage with the story as it develops.

Grounding with prompting

Improving prompts doesn’t just mean writing instructions! The prompt design process should consider the input, the instructions, AND the output.

The LLM isn’t going to be able to simulate the world. But it should try. The story should feel grounded in a full, imagined world. So while it writes a “story” that is presented to the player, it should simultaneously maintain a more objective description of the basic environment and plot advancement. Where is the player located? Are there details that haven’t been revealed? Backstories, secret tensions, physical layout, etc. I’ve described very involved ways of maintaining this, but it can be much simpler, like an initial description and log of changes (written in natural language) with occasional rewriting into a single description.

A general principle I have is that LLM developers should value the reader’s effort more than the LLM’s. If you aren’t generating more material than the reader is consuming then you are doing it wrong.

A simple prompt improvement is to have the LLM write out the basic facts of the world before generating the next passage: where is the player character, what is their physical placement, who else is there and what are their mutual relationships? Force the LLM to answer these basic questions before progressing the story. (Some of this is discussed in Intra: Guided thinking.)

Choice generation

Choices need to be much more engaged with the plot, and less with the character. The plot drives what is important and pivotal. The character is navigating those choices, and character traits are going to come out in the resolution of the choice.

When the LLM is tasked to generate choices it should simultaneously be generating the outcome. Not necessarily the entirety of the outcome (prewriting all branches), but at least a one-sentence summary and next passage. This is how a good author would write choices: a good choice has an interesting consequence. It’s also a chance to decrease the latency since you can immediately show that next passage while more content is being generated.

The story passages must also support the choices. Hidden Door generates the passages between choices with a good length (feels like one beat), but they don’t lead into a meaningful choice. Again this requires writing ahead: outline the plot given guidance on what makes a good choice point, then generate the actual story text given that outline. Even one or two sentences of outline will allow the LLM to do something closer to writing backwards from the choice point.

I wrote some more thoughts about choice generation in Roleplaying driven by an LLM: Interface and interaction

More kinds of choices

You can give choices that have no (immediate) affect on the story, but do affect the character. For example: “X happened, how did you feel about it? (a) frustrated, (b) incensed, (c) accepting”

You can ask that question while more passages are being generated, and simply file away the answer for later use.

You could also allow the player to inspect different elements of the environment. These passages could be pregenerated to make it responsive while also being optional. If the player never inspects something then the description doesn’t become canon (or maybe it does, the freedom lies with the game designer).

Plot development

Plot development happens at many scales: the satisfying conclusion of a work, broad themes, plot arcs; at a smaller scale there are different tropes to engage, setup and delivery, rhythm and pacing.

The game currently has a broad arc that appears prewritten: you arrive in Oz, you must see the Wizard, you meet your companions, and so on. It’s fine that these are prewritten, and it doesn’t mean that you can’t work on generating the arcs in a later version. Handwriting or hand-editing content is productive scaffolding both for the LLM and for the narrative designer.

I don’t yet have an intuition of how to handle the broadest scale of plot development, but there’s still a lot to be done on the small scale. Commit to outcomes before prose. Treat each passage as a small contract with the reader that the model must honor.

Research the field

Generally the story structure should learn more from existing narrative design, especially in visual novels and choice-based interactive fiction. There are hundreds of games in this genre, many quite popular, so this is not new ground and there’s lots to learn from. These days I regularly turn to AI-generated deep research when I want to know more about an area like this. For example:

- Narrative Design in Choice-Based Interactive Fiction and Visual Novels (which I generated for this post)

- Generative Storylines and Story Grammars (which I generated previously for myself)

Even though I have only passing familiarity with this genre of game and its terminology, and know nothing about the major players, Deep Research lets me ask the questions and express the tensions I’m feeling without knowing how to name the solutions. This is especially effective with prompting because many of the things I learn can be translated directly into prompts.

Start with static generation

We can step back and ask the question: how would I approach the entire game development process?

While writing this I have come to believe the right approach is to start with choice-based fiction, entirely pregenerated in a static form.

There is something magical about a fully responsive game, but pregenerating the game means you can focus on the entire arc of a story, learn both the narrative and prompting patterns required, and explore the space holistically. Making that generator incrementally more responsive and dynamic seems like a feasible path where story quality is prioritized. Story quality should be the priority.

Hidden Door includes the (very common) approach where you are given choices but also have the ability to type your own choice. This feels essential to get the full benefit of an LLM, to make it fully responsive and engaged, but I’m unconvinced. Player input is the perfect place to prompt-hack the story (which is trivial in Hidden Door and every other LLM-based game of this genre). You’re only hacking your own story, so whatever, but the ability to hack the storyline makes the story feel less impactful; you can always bend it whatever way you want. It also takes pressure off of the task of creating good choices. But the choices should be good!

Also: the choices are only as interesting as the passage leading up to the choice. Free text player input won’t fix that.

Character consistency & pronouns

When you have programmatic control over some game setup, you should use that to make sure that the setup is consistent. Currently attributes can overlap (like “friendly” and “rival”), and genders and pronouns can disagree. The avatars are also inconsistent, though I suppose the LLM never sees them.

Any inconsistencies make the LLM’s work harder. It becomes easier for it to lose track of characters and relations. The mistakes that emerge often don’t point directly to these inconsistencies, but are the result of a generally confused LLM.

The game also includes three pronoun options: she/her, he/him, and they/them. Pronouns are the right way to address gender for an LLM: the LLM is writing lots of text, and pronouns are exactly where gender is introduced into text; what’s in the character’s pants is far less impactful. But they/them doesn’t have the intended effect, it does not lead to a non-binary character. Instead the gender is simply indeterminate. If I say “Alex is great, I love what they do” that’s a non-binary pronoun. But for the LLM they/them is like what you’d find in an employee handbook: “before the employee returns to work they must wash their hands.” This does not imply the employee is non-binary, only that the gender is unspecified. Much of what an LLM does is like a dream; for instance in a dream you can encounter someone who doesn’t have a face. It’s not that the person’s face is blank, it’s that the face simply doesn’t exist because you didn’t observe it. In the same way they/them is just an incomplete character.

You can have a non-binary character in an LLM-generated story, but it requires a strong positive assertion of their non-binary gender, not a passive use of indeterminate pronouns.

Latency

Often I’m been pretty lazy about latency in my own LLM work. Quality is most interesting to me, and I don’t want to do a premature optimization by prioritizing latency over quality.

But I think the ideal player experience for this kind of game is a casual, relaxed reading experience. When the game makes a choice feel effortful the entire reading process feels effortful. Meanwhile my other suggestions for prompting will only make the latency worse!

That said, the pace of the interface doesn’t have to align with the tasks given to the LLM.

An example prompt

I imagine a prompt that looks a like this:

You are writing a story in collaboration with the player, set in the world of the Wizard Of Oz.

{story context, world lore, character descriptions, etc}

{the story as it has progressed, linearly}

<playerChoice character="{playerCharacterName}">

{whatever the player last chose}

</playerChoice>

<passage>

{the pre-generated passage that immediately follows the choice}

</passage>

<consequence>

{a summary of the consequence of the choice, as generated alongside the choice itself}

<consequence>

----

You will continue writing the story in this form:

<context>

<!-- describe where {playerCharacter} is. What other characters are also present? Describe the relationship between {playerCharacter} and each other character. What dramatic tensions need immediate resolution? -->

</context>

<outline>

<!-- Outline the next part of the story. Include:

1. Consequences from the last choice. Make it impactful, so the player feels like they are driving the story!

2. Describe how any other characters present will react or feel about the choice

3. Does this resolve {currentObjective}? If so, then say "YES" and describe how. If it makes the objective impossible then say "IMPOSSIBLE" and describe how. Otherwise say how it affects the objective and what remains to achieve the objective.

4. What happens next?

5. What is the next pivotal moment where the player (as {playerCharacterName}) can make a consequential decision?

6. Are there opportunities for the player to make small decisions about: how {playerCharacterName} feels about what happened? A small preference the player can identify for {playerCharacterName}? These are choices that don't affect the plot development.

-->

</outline>

<passage>

<!-- Write the story from {playerCharacterName}'s perspective as a series of short paragraphs -->

<smallChoice>

<option>

<!-- Optionally a small choice for the player to make -->

</option>

</smallChoice>

</passage>

<choices>

<!-- Make three choices: -->

<choice number="1 or 2 or 3"

title="<!-- From {playerCharacterName}'s perspective, what are they choosing to do? -->">

<passage>

<!-- One paragraph redescribing the choice -->

</passage>

<difficulty>

<challenges>

<!-- Describe the challenges to success -->

</challenges>

<playerAssets>

<!-- Describe what helps {playerCharacterName} succeed -->

</playerAssets>

<success>

<!-- Use the d20 roll to explain why it succeeds or not, finishing

with SUCCESS if it succeeds, and FAILURE if not -->

</success>

</difficulty>

<consequence>

<!-- One sentence describing the consequence of the choice -->

</consequence>

</choice>

</choices>

Generate three choices. There are three rolls:

1. d20 roll {roll1}

2. d20 roll {roll2}

3. d20 roll {roll3}

When the player makes a choice:

- Construct the prompt to generate the next section of the story, sending it to the LLM

- Display the passage that is already generated

- Indicate success or failure

- As the response comes streaming in, display any

<passage>elements as they come in. - When the

<choices>element is fully produced, shuffle the choices and present them to the player.

I put in <smallChoice> but it will be tricky to balance: either the LLM will always create those choices or never. You could roll a die and suggest it include a choice or not based on the die. That will put a kind of quota on choices, but won’t let the choices be added intelligently based on plot. Another option is to let it always create choices but include a decision process in the choice that can void the choice (then the UI never shows voided choices to the player).

The prompt also needs some examples, though if you prime it well then you can use the story context itself as a kind of example. You might need some occassional verification to ensure it doesn’t go into a feedback cycle where it goes off the rails. But symmetry between input and output can be very effective in efficiently providing both history and examples at the same time. There are a few options to bootstrap these examples, creating the initial examples before the story has started:

- A combination of handwriting and programmatically setting up the initial context. Things like character setup can be presented as choices (even if the UI shown to the player is different).

- Use a rough template of the setup and feed things like the initial character and some random elements into an LLM, letting it instantiate the template. You might want to use a more advanced LLM to make sure it starts on the right foot.

- Give extensive examples and instructions during early story setup, while dropping those later when the story is a self-supporting example.

There are also some notes on how to turn this into a chat log in Intra: role:user.

Conclusion

I do wish Hidden Door well. This is stiff criticism because I wish them well.

It’s easy when creating AI content to be a little too enamoured with the novelty. It feels magical. But if you keep interacting with it the novelty wears off, and you should plan for after the novelty wears off. In this case that means a stronger engagement with the process of storytelling. You have to encode the writing process into the prompting:

- Track and commit to a world state. (The reader is maintaining a world state in their mind, don’t break it!)

- Outline before writing the final prose.

- Have the model articulate generalities, finding themes in the details instead of revisiting every detail as though it is meaningful.

- Decide on consequences before choices. Choices are a mechanism to change narrative direction, so work backwards from interesting directions.

- Optimize story progression for fun choices! (And think hard about what makes a choice fun.)

- Ensure you can put together a cohesive and entertaining story before opening the sandbox.

- Allow consequential failure. It doesn’t have to be story-ending, but it should disrupt the story and the world state.

It’s a lot, but I think this is all fun work… using an LLM means you can think about the systems and cognitive processes that lead to a good story and then try to actually implement them. It’s a new and strange kind of science.